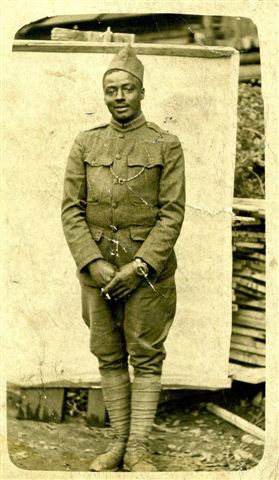

A photo of my maternal great-uncle Clarence Holmes Suber at 26: there are solid

indications that the photo was taken in France: he is wearing the puttees leggings, and the overseas cap was French-made for Americans.

Because he doesn’t wear the chevron on his sleeve indicating 6 months overseas service, the photo was taken at the beginning of his tour in France;

he arrived in late April and earned the six-month chevron in October, just weeks before the Armistice. Because he took part in the great Champagne offensive that began on September 26, 1918, this was probably taken before he entered the hellish trenches, late spring or early summer.

This article is dedicated to his niece, Flora L. Cherot 1920-2015, whose ongoing recitation of his story made this possible.

|

CLARENCE SUBER

March 15, 1892 - March 21, 1925

An innocent young man sent to war. The dangers, ghastliness,

and the unhealthiness of trench warfare that World War I soldiers experienced were hard to sustain; war devastates the people who fight them as it does all else it ravages.

|

|

Clarence was born in Columbia, the state capital of South Carolina, one of 4 sons and 3 daughters. His parents, who were born into slavery and freed as toddlers,

came from rural areas: his father Drayton Nance Suber was from Laurens, Newberry County, his mother Nancy Green Suber was from Blythewood, Richland County.

His high school years were at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute from 1906-08 and part time as a junior in 1910-11, studying carpentry; his mother had heard Booker T. Washington

speak and enrolled him and his brother Andrew, who learned tile work there.

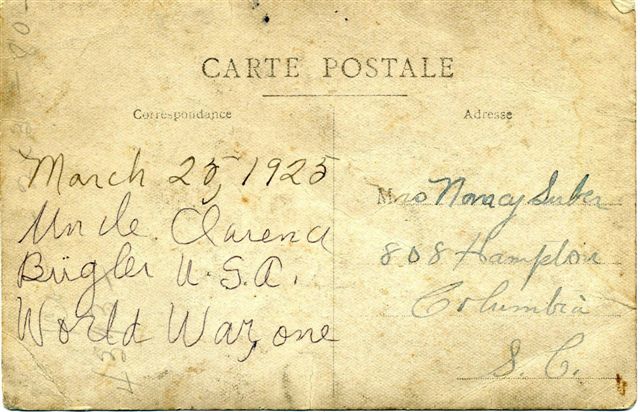

CARTE POSTALE

|

This is the other side of the army photo of Clarence, which is the only surviving photo of him; the original image is 4 ¼”x 2 ¼“.

His death certificate states he passed away in Tuskegee, Macon County, Alabama, at the US Veterans’ Hospital after being treated for 132 days, on March 21, 1925, at 11:55 AM, six days after his 33rd birthday.

The cause of death was "Tuberculosis, Chronic, Pulmonary;" where the disease was contracted, what contributed to it, or its duration were listed as “Undetermined.” He was buried at Douglas Cemetery in Columbia on March 24th,

where his mother and a younger brother Isaiah were later buried.

The date written on the Carte Postale, March 25, 1925, is the day after his burial. It was addressed to his mother in a different hand than the one on the left. Judging from his Draft Registration Card neither appears to be in his handwriting.

“Uncle Clarence,” could be in his mother’s handwriting because she often referred to her sons as “Unc,” says Flora Cherot, his niece, or one of his sisters could have written it. “World War, one,” may have been added later, since the war was

initially called “The Great War.” If the writing was added later, it could have originally been sent in an envelope or through Army mail, needing no stamp. There are two personal details in the photo: he’s holding his cigarette in his left hand – was he left-handed? And there

is a ring on a chain that runs from his left pocket button to his right pocket; whose was it?

|

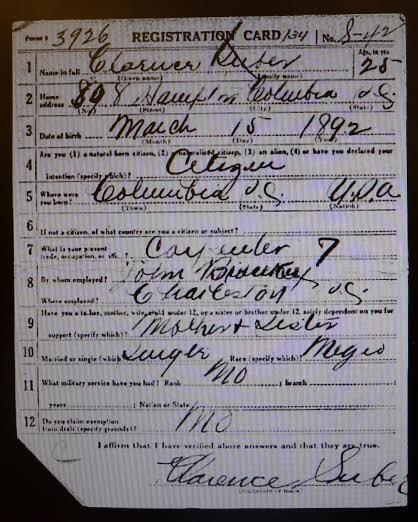

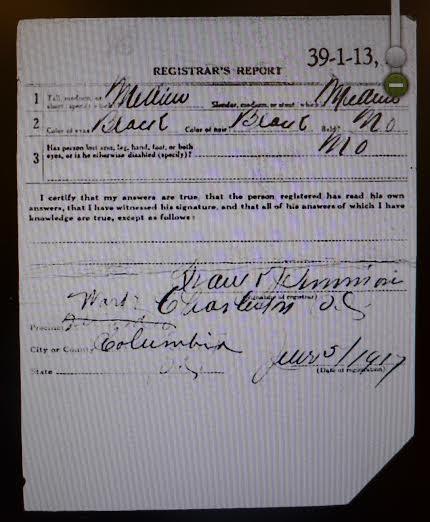

CLARENCE'S DRAFT REGISTRATION

| |

The front side

|

|

|

|

The reverse side

|

Clarence’s family posted a memoriam to him in the March 29, 1930 issue of The Palmetto Leader, pg.7, five years after his passing:

IN MEMORIUM

SUBER -In loving memory of our son and brother, Clarence Suber, who died March 21, 1925,

Just a line of sweet remembrance,

Just a memory fond and true,

Just a token of love and devotion

That our hearts still hold for you,

Mother, father, sisters and brothers

His mother installed electricity and other modernizations for their house in Columbia from his Veterans’ benefits. Nancy Suber said she regretted praying for those improvements that came through the death of Clarence, her favorite son. His death certificate lists a Ruth Suber (was that her ring?) as his spouse, yet his benefits went to his parents. Was Ruth a common-law wife without legal claim?

Clarence was a draftee who tried to avoid fighting "Over There:" his Draft Registration Card lists his mother and sister as dependents who actually lived with his father Drayton Suber in Columbia, while Clarence lived in Charleston when he made that claim.

According to his personnel records, upon entering the service, Clarence stood at 5'8", and weighed 157 pounds; he was 20/30 in his right eye; and he had an "over-arching" big toe. That he had "Excellent, " and "Very Good" character is mentioned many times,

which is consistent with his mother's and siblings recollections of him. Before the war as a "Hand Carpenter" and "Chaffeur" he made $24.00 weekly;

as a soldier he was paid $1.25 per day, for a total of $377.50 for 302 days; he was not paid during training. He was designated Bugler on April 3, 1918, 3 days before he left for France on board the troop transport President Grant.

|

CLARENCE SUBER, BUGLERPhotos on papyrus, © Amir Bey, 2014

He must have felt pride with the distinction of being a soldier. He was a Bugler, Company B 371st Infantry 93rd Division, service #1872417: “The “Bugler from Company B.” A bugler usually held the rank of corporal, probably playing Taps and Reveille and other calls at camp. After arriving in France, Clarence’s duties were likely as a messenger

between regimental headquarters and the line with little bugle-playing, or possibly a "Runner," carrying messages between positions in the trenches and headquarters. His mother wondered where he learned to play the bugle.

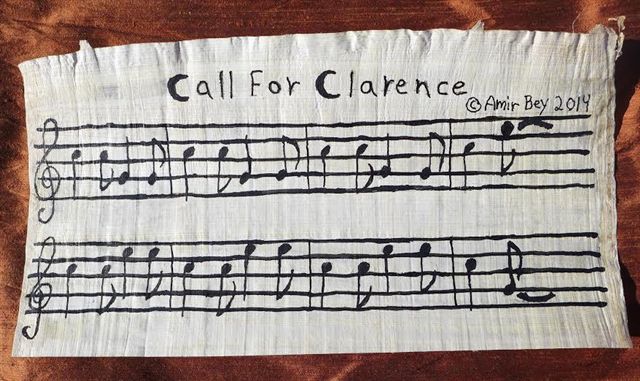

I wrote a bugle call dedicated to Clarence, Call for Clarence:

India Ink on papyrus © Amir Bey, 2014 |

|

|

CALL FOR CLARENCE

|

RACISM IN THE US MILITARY DURING WORLD WAR I

In letters home Clarence described how wounded white soldiers were given coffee and cigarettes by the Red Cross, while wounded Black soldiers weren’t, telling his mother not to support those organizations; the YMCA sometimes excluded Black soldiers from their hospitality centers. His descriptions of preferential treatment for white soldiers by those organizations are supported by personal accounts and recent views on the bigotry that Black soldiers faced.

The “Rainbow Division,” so named for its inclusion of 26 states, denied the 369th Regiment entry because “Black was not a color of the rainbow.”

During the war the French military and municipal governments were warned about exposing African Americans to equal treatment, that it would complicate their return home. While white American soldiers enjoyed freedoms and end-of-war bonuses, soldiers of the "Colored" 92nd and 93rd Divisions were given none.

There is literature about African American soldiers of the 371st written by white officers that is positive, but the hardships that African Americans endured at the hands of the military, including late pay, rushed training, poor equipment, and the degradations and dismissals of Black officers was overwhelming. Nevertheless, the 371st’s training at Camp Jackson, their transition from American to French methods, and their heroic feats in the trenches demonstrate their resilience and adaptability.

After the war, Lieutenant John B. Smith, a white officer, stated:

“The French people could not grasp the idea of social discrimination on account of color. They said the colored men were soldiers, wearing the American uniform, and fighting in the common cause, and they could not see why they should be discriminated against. They received the men in their churches and homes.” From The American Negro in the World War, by Emmet J. Scott, 1919

The enforcement of racially motivated regulations and tasks made the uniforms of African-Americans not only military, but penal; after the Armistice African American soldiers were put on a tight reign, the military preventing them from interacting with French people – too much of a taste of equality with whites, and no mixing with the French women! Clarence's mother told how returning African American soldiers ran into trouble when policemen in Columbia found photographs of them with French women.

THE 371st REGIMENT'S WWI HISTORY

The 371st was organized on August 31, 1917 giving the 93rd Division the 4 regiments that made up American divisions. The 371st's formation was delayed until autumn because hands were needed for the cotton harvest. Training was at Camp Andrew Jackson, just outside of Columbia. He was one of the few from an urban area: the bulk of the 371st recruits were from the cotton fields, uneducated, not familiar with military drills or basic health practices such as dental care. – Clarence himself was missing 13 teeth when he was drafted.

The 371st Regiment was made up of draftees, unlike the 3 other "Colored" regiments in the 93rd: the 369th the fabled Harlem Hellfighters; the 370th (the Illinois 8th); and the 372nd, (from different states), were all National Guard units. Although the regiment did not have the history, training and education of the other three regiments, it performed remarkably well equaling the other regiments in battle.

Reasons for their comparative lack of recognition is that they were not national guardsmen with previous histories;

and after the war's end did not march up 5th Avenue in New York City (369th), or mobbed in Chicago (the 370th), nor did they have the likes of Lt. James Reese Europe's 369th Regimental band touring France bringing audiences to tears, traveling over 2,000 miles and 100 cities.

| |

The 371st's Crest

|

|

|

|

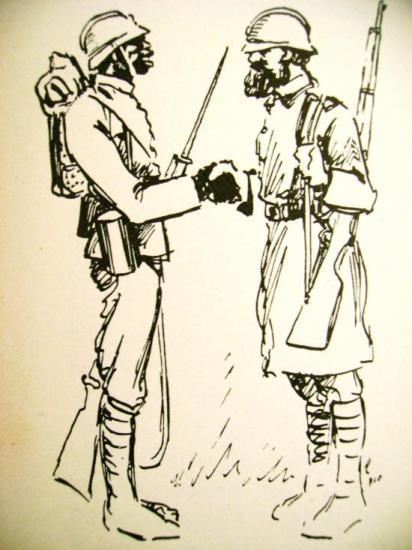

Buffalo Soldier meets the "Poilu"

|

The crest commemorates the regiment’s consolidation of the "Buffalo Soldiers" with the French Army. It was not used by the 371st during WWI,

but was later adopted and approved for the regiment on March 3, 1950. The combination of the Fleur-de-lis and the black buffalo for the

Buffalo Soldiers parallels the illustration by Lester D. Dickson of an African American soldier wearing the French helmet shaking hands with a French soldier

that appears in Negro Combat Troops, by Chester D. Heywood.

|

|

Messengers of the 372nd Regiment, one of the regiments in the 93rd Division (Colored) - that's how they listed it, "Colored"; From Emmet J. Scott’s The American Negro in the World War; Although Scott calls them a motorcycle corps, only one soldier standing in the center has a motorcycle,

the rest are holding bicycles. Note the combinations of French M15-Adrian and US M-1917 helmets. Could they denote different regiments?

The 371st was the last of the 93rd Division’s regiments to arrive in France, leaving from Newport News, VA, on April 6 (some records say April 7), on the President Grant troop transport, and debarking on April 23, 1918, at Brest, in Brittany, France.

- He is listed in records as being designated Bugler on April 3rd.

The baffling illogic of segregation - African Americans fought the war as part of the French army - the US military did not want Black American soldiers serving alongside whites, preferring either the English or French armies incorporate the 93rd into their armies.

The English refused, the French, who used colonial troops from North and West Africa, agreed, and it was reorganized as a French unit; the other Black division, the 92nd, was also incorporated into the French Army.

This was a shock for the 371st’s white commander, Colonel Perry Miles, who received this information from the French upon arrival. The African American soldiers wore parts of French uniforms such as the blue jackets instead of the American kaki, the French M15 Adrian helmet, while the accurate long-range US Springfield rifle was replaced by the inferior French Lebel rifle,

the French relying less on rifles than on machine guns, automatics and the bayonet.

THE RED HAND DIVISION

|

|

From a drawing by General Mariano Goybet

After training in the new French equipment and tactics from April 26 to June 6 in the vicinity of Bar le Duc, it joined the French 68th Division on June 13, near Verdun. From June 23 until September 14th it was on the line in the Verdun Sector.

It fought as part of France's veteran 157th “Red Hand” Division, 9th Army Corps, which had been decimated after the battle of Chemin des Dames and in need of reinforcement.

It was reconstituted by putting together the 333rd Infantry Regiment (French) with the American 371st and the 372nd American Regiments. It was under the command of General Mariano Goybet, who was later awarded the US Distinguished Service Medal.

|

HILL 188

|

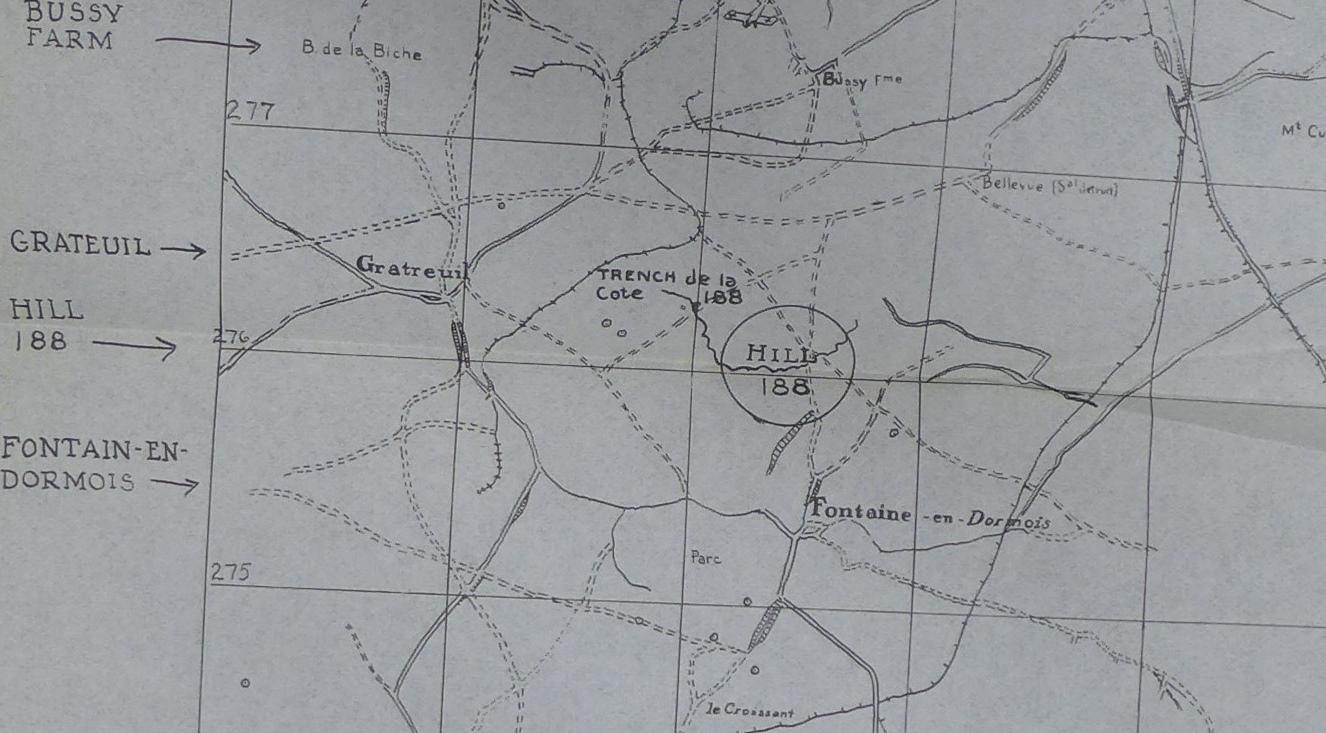

Clarence was in the great offensive on the Champagne front from September 26th until October 6. The 371st took Côte (Hill) 188, Bussy Ferme, Ardeuil, Montfauxelles, and Trieres Ferme near Monthois.

The map above shows the hill and other objectives of the 371st during the great fall offensive. Note the little sketch of a downed airplane at the top center. It was the only plane known to be shot down using rifle fire, by the 371st.

|

|

From a drawing by Lester D. Dickson appearing in Negro Combat Troops, by Chester D. Heywood.

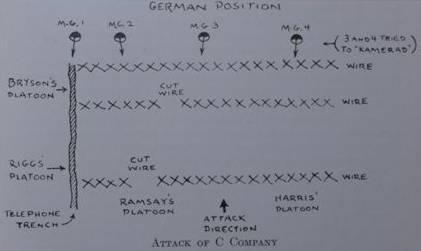

During the offensive, the French 2nd Moroccan Division and the French 161st Infantry Division had advanced creating a space between them, and the 371st had to fill in the gap, advancing in a North-easterly direction.

Hill 188 was formidable: surrounded by valleys with a trench running through it, it was well fortified by the Germans with a complex series of machine gun nests in concrete bunkers and pillboxes woven extensively with thick barbed wire, and artillery emplacements.

A German sergeant along with dozens of soldiers surrendered and gave information that the defenders were leaving the area, leading Colonel Miles to think there wouldn’t be much of a fight. When some of the 371st‘s 1st Battalion, which included Companies A, B, and C, approached the hill, they were met with artillery fire. After they made slow but steady progress the Germans through vocal and hand signals indicated they wished to surrender.

When Company C reached a certain point, the Germans blew whistles and subjected the company to intense maching gun fire, almost annihilating Company C.

The survivors of Company C and other companies including Clarence’s Company B regrouped and by firing on the Germans’ flanks and hand to hand fighting with bayonets and knives, exacted severe revenge on the Germans. Company B’s fighting was called “gruesome,” with even the machine gunners begging for mercy.

This engagement took place during the final offensive that defeated the German Army. How can we imagine Clarence at Hll 188? Was he running messages through the communications trenches between his company commander and headquarters, or fighting at close quarters in the trenches? The messages between General Goybet and the 371st Infantry Commander Col. Perry Miles read "How sent: Runner."

Were they sent by foot, or motorcycle? Here is an account illustrating the dangers to runners by Frank Washington of Clarence’s Company B; whether or not it was Clarence, it describes what he may have experienced:

"The German artillery fire was accurate. They had our ranges down to a science… They were good marksmen. Why, I've seen them cut a regular ditch along a row of shell-holes to prevent our troops from using the holes for shelter.

There was positively nothing they didn't do that was horrible. I've seen them cut loose at a company runner with three-inch artillery. It was a funny sight for us, but not for the runner. The Huns would drop shells all around him while he fled on wings of terror. I never saw them get a runner with their artillery fire, but I've seen some very close shooting.”

During the final offensive the 371st captured many German prisoners, 47 machine guns, 8 trench engines, three 77mm. field pieces, a munitions depot, many railroad cars, and large quantities of lumber, hay and other supplies. It shot down three German airplanes by machine-gun and rifle fire during the advance, which no American unit accomplished.

In the fighting between September 28 and October 6, 1918 it suffered large casualties: 1,065 casualties out of the 2,384 engaged occurred during the first three days, the highest along with the 369th. The 371st was the most forward unit, the “apex of the salient” of the attacking army in this great battle. It had the most decorations of the 93rd Division,

receiving unit and numerous individual citations. For its tough fighting in the Champagne offensive, the entire regiment was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm; three of its officers were awarded the French Légion d'honneur; 123 men won the Croix de Guerre, 26 earned the United States Distinguished Service Cross, and Corporal Freddie Stowers of the regiment's 1st Battalion,

was the only African American soldier from World War I awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously in 1990.

This monument to the 371st Regiment is near the French towns of Ardeuil and Séchault; its top was damaged by artillery during World War II.

The 371st was pulled from the line on October 6, to the Alsace Sector, Vosges, staying there from October 16, until the Armistice on November 11 then withdrawn on November 15, proceeding to Le Mans Embarkation Center, leaving France from Brest on the transport Leviatian February 3, 1919, arriving in Hoboken, NJ on February 11, disbanding after arriving in South Carolina. Clarence was discharged on February 24th.

Casualty lists do not include Clarence's name, suggesting that he wasn’t shot or gassed. The psychological wounds that Clarence suffered, along with the TB that he likely contracted in the trenches were not tabulated the way being wounded or killed in battle was.

Although he was fighting mainly during the warmer months he was in North Eastern France where nights could be cold and wet. Clarence wrote about the privations of the trenches, the cold, the rats, and other hardships. Being exposed to those conditions permanently affected his health, and while he only fought for 5 months and stayed another 3-4 months, he returned home sick never recovering, dying less than 5 years after the Armistice.

|

|

CLARENCE SUBER

|

|

|

|